Why Meta’s move from friends to virality is an existential threat for Facebook

Full opposite Art of War, here we come

Will Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s fight with another company over the future of media cost him his own? Just maybe, if reaction to his latest changes to Facebook is any indicator.

“Yesterday, I clicked to ‘see less’ 44 Facebook posts [including] all of the videos from sources I do not follow,” Facebook friend and author Shel Israel posted recently. “This morning, I clicked ‘See Less" 62 more times.”

“This is spam and it's coming from Facebook.”

Zuckerberg has decided to fight fire with fire. Most downloaded app of 2022 TikTok is easy, instant, and glues users’ eyes to smartphones for hours at a time thanks to algorithms that predict what cute cats or sports plays or fail videos you’re most likely to want to see. In response, Zuckerberg has decreed that Meta will double its AI content recommendations in both Facebook and Instagram.

But that strategy ignores what made Facebook nearly invulnerable for a decade.

Facebook hasn’t always had the best content or the best interface or the best user experience. It’s arguably harder to use than fresher, younger upstarts, with dozens of options, tabs, and controls in the app on any given screen. As the OK Boomer of social networks it’s just not at all cool with the kids anymore, and the company lost most of its luster with older generations too in multiple repetitive privacy fails — highlighted by the massive Cambridge Analytica scandal — and fake news content moderation policies applied in sometimes quixotic and often controversial ways.

But from the very beginning, Facebook has always had one thing: the friend graph. Your people are there.

Upstart social networks have been a dime a dozen for a decade. “Facebook for this vertical” and “Facebook for that demographic” have been media and investor pitches for just as long. But in a very Yogi Berra-ish “no one goes there nowadays, it’s too crowded” kind of way, everyone who left for the shiny new glitter of competitive social networks eventually had to sheepishly come back to Facebook because that’s where Mom and Uncle Dale were.

They just weren’t going to stick with NewAwesomeSocial app.

Because a social network without your social essentially sucks.

TikTok took a different approach. TikTok is winning because (appropriately, as a Chinese company) it adopted a very Sun Tzu Art of War approach: don’t attack your enemy’s strong points, attack your enemy’s weak spots. Rather than try to recreate the social graph that everyone and their dogs had tried and failed to do, TikTok simply created a way to optimize its ability to show you something you like, nearly every single time you swipe your greedy little thumb up.

Forget friends.

Embrace virality.

Zuckerberg, seeing TikTok’s rise, has responded how he has always responded to business threats: copy and paste. Facebook’s and Instagram’s Reels are TikTok inside a Meta app. And now the hallowed news feed, which the company has been experimenting with for years, is getting an injection of TikTok too.

In other words: stuff that Facebook thinks you’ll like, from people, brands, and influencers you have not explicitly chosen to follow.

That’s a challenge to our psyche, says Seth Berman, a VP of Marketing at Contentful, because it changes the implicit contract we have with our social entertainment platforms.

“Users see the Instagram feed as a mirror. Though algorithmic, it's nonetheless a reflection of one's friends and selected accounts. When it starts showing weird things, users react emotionally because they identify with what they see in their feed. In contrast to TikTok which was entertainment from the start ... users never identified with TikTok content.”

Even more, it’s a challenge to Meta’s supremacy, because it moves the fight with TikTok from where Facebook is strong to where TikTok is strong.

In other words, it’s doing the exact opposite of what Sun Tzu’s Art of War suggests.

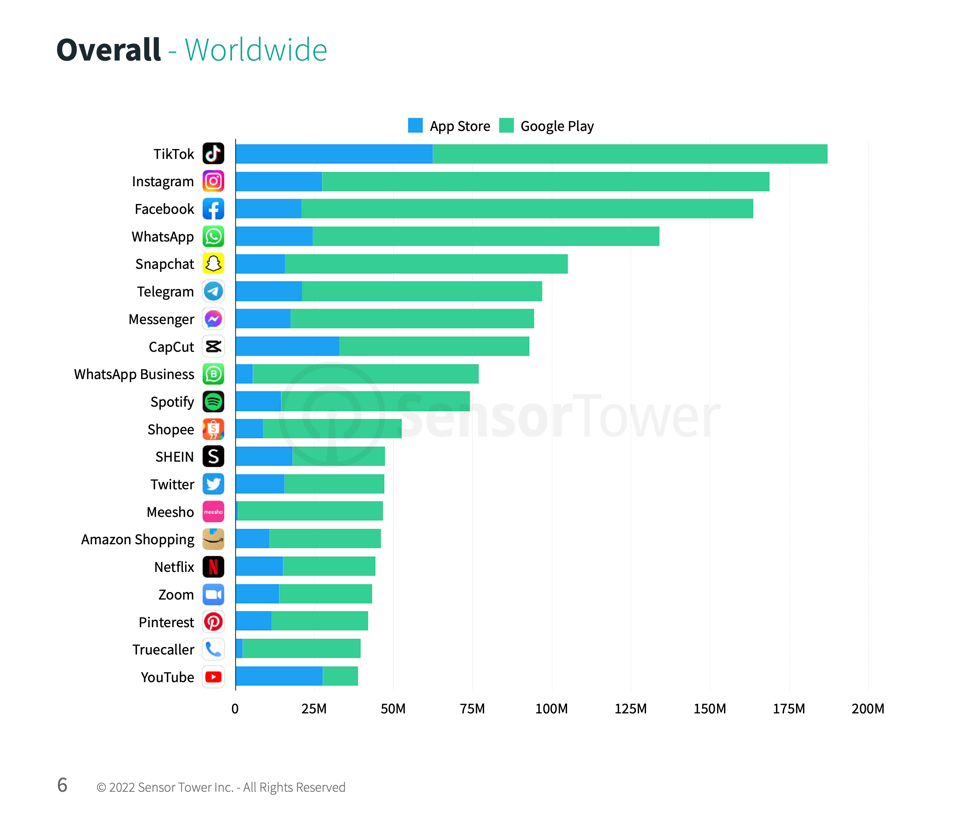

Look, Facebook is still immensely powerful: much more powerful than TikTok. In SensorTower’s Q2 data digest, TikTok was the most-downloaded app. But Meta owns Instagram, Facebook, WhatsApp, Messenger, WhatsApp Business ... five of the top ten most-downloaded apps.

Put it this way: a full 50% of the top ten apps are owned by one company. That’s global domination.

Of course, in a very Silicon Valley way, Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg is following Intel founder Andy Grove’s advice: only the paranoid survive. To win, you must crush the life out of the upstarts. (Or buy them young, like Instagram and WhatsApp.)

But when Zuckerberg abandons the friend graph, he leaves the high ground. He razes his own fortress. He sacks his own city.

In addition, something that is everything is nothing. Facebook (the app) is already partly YouTube (the video tab that won’t stop playing until you physically stop it), partly TikTok (reels), partly Craigslist/eBay (the Marketplace tab), partly games, partly memories, partly events, partly shopping, partly message boards (groups), and partly social network (the main friend feed), among other bits and pieces of digital flotsam and jetsam that Zuckerberg has crowbarred into this creaking, lumbering, tottering old app.

So what is Facebook?

Apparently, for Zuckerberg, anything that captures billions of peoples’ time and attention in any way necessary. Everything must be available so all will never leave so Facebook can sell our attention more and more to an ever-growing clientele of brands and corporations.

Of course, this is arguable.

One might say that the friend graph is a perishable asset, and they’re right. Because Facebook (the app) has not really captured younger generations and Instagram (which has) has always been a little less about friends and little more about interests, the older generations that glommed on to Facebook to share baby photos and engagement photos and vacation photos will eventually age out.

But sure that time is not immediately imminent. And surely there are other ways of extending the friend graph to younger generations ... if Meta had an ounce of creativity and innovation, rather than a hefty dose of “Redmond, start your photocopiers,” as Steve Jobs’ Apple always accused Microsoft.

The problem with the virality feed versus the friend feed is that anyone with some scale can do it. Twitter can do it. TikTok has mastered it. YouTube is doing it very successfully. Dozens of TikTok copypastas are doing it. Triller is doing it.

There’s no moat besides scale, and multiple other companies have scale.

For some, the shift away from the friend graph is inevitable.

“It’s an inevitable shift for viral social content to extend beyond the boundaries of one’s social graph,” says Adam Landis, founder and CEO of AdLibertas. “Let’s be honest, an outlandish video involving strangers is frankly more entertaining than a humdrum video of your friends. It’s the reason we gravitated towards Facebook in the first place: it was more fun to look at the exciting pictures of extended friends, than to flip through aunt Marge’s photo album.”

Landis sees a possibility for Meta to merge the friend graph and the virality ?graph? in a powerful way to emerge out of the shadow of TikTok’s threat even stronger.

“If Facebook can thread the needle of retaining user social graphs and capture the zeitgeist of surfacing global social content they stand to win,” he says.

That has to be CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s plan. But it’s not without risks, and not least of those risks is a user rebellion.

“The more Instagram blurs the line with algorithmically curated content and friends content, the more users will feel isolated and Instagram will lose them,” says Rebecca Caulkins, a marketer at Pixelberry Studios. “I also believe the more Facebook separates the two, the better retention the platform will have. Meta might temporarily see monetization growth on Instagram but for the long term I do believe they will see users drop off and switch to more peer to peer focused social sites like BeReal. This is from my perspective as someone from a younger generation who has been an avid Instagram user for years.”

And that’s the challenge.

The other challenge? Facebook’s not really very good at virality yet, and especially not very good at mixing it effectively with friend content.

“I liked an interesting video of a whale following a guy on a kayak,” says Shel Israel in another Facebook post. “The next thing I know I am bombarded with videos of adorable animals. I like a comment by someone I don't really know and now I am drowning in that person's friends at the expense of seeing my own friends.”

“My sense is that [Facebook has] tweaked how much [its] AI decides, and [its] AI still lacks a lot of common sense. If [Facebook keeps] going on your current trajectory, I'm wagering it will result in [its] demise as the leading social network.”

There is one way of seeing fewer recommended posts, a mutual friend responded: get off Facebook. Which, frankly, has become more common in my particular friend circle. That, of course, is the nuclear option, and it’s the nuclear option that Zuckerberg and company are very much attempting to avoid.

But trying to thread the needle between TikTok-style virality and old Facebook-style friend feed is proving challenging, at least in the early going. And it risks more and more abandonment of Facebook by its users. The question is: does Meta care about losing some of its existing audience as it pursues both new audiences and an ever-larger share of time from those who will stay?

And: will Meta win more than it loses by making the change?

“You seem to be laboring under the misapprehension that Facebook cares what their users think,” one of Israel’s Facebook friends responded to him.

There is another way Meta can still win, of course: through the courts. Sentiment against China and Chinese apps is high in the U.S., and TikTok has already been banned from the soon-to-be most populous nation on the planet, India.

“If the tides are really turning on TikTok and the U.S. government gets involved due to data concerns, Meta might be positioned to fill the void if the number one choice is made unavailable,” says Sam McLellan, CMO at BigBrain Games.

That’s not the way most leaders want to win, at least not publicly.

But some, of course, want to win at any cost, in any way.